PUKULAN TJIMINDIE

Pukulan Tjimindie

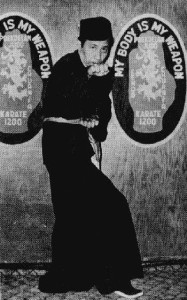

Willy Wetzel was a Dutch-Indonesian who studied under Mas Jud and went on to teach his art under the name Pukulan Tjimimdie, making his way eventually to the Pennsylvania in 1956. This art combines the principles of Cimande, Sera and Cikalong, along with the 5 animal styles of Monkey, Tiger, Snake and Crane. The fifth animal is the Naga or Dragon and this is considered to be a culmination of all of the animals. Below is an article written by Willam Sanders teacher Guru John Malterer. Guru John Malterer was a direct student of Master Willy Wetzel. The information below is consistent with research done by Guru Besar Jerry Jacobs with the family of Master Wetzel.

Written by Guru John L. Malterer

Poekoelan Tjimindie means beautiful flowing waters. Nothing is weaker than water, but when something hard or resistant stands in its way, nothing will alter its course. Movements blend imperceptibly from one into the other, like waters of a river, endlessly flowing, without a momentary opening for the opponent. Willy John Christopher Wetzel (1921 - 1975) was my teacher of the Chinese-Indonesian Poekoelan Tjimindie fighting arts. He was born of Dutch and Indonesian parents in the village of Loemadjang on the island of Java. Mr. Wetzel began informal training in the fighting arts at the age of seven from his father. He began formal instruction in 1935 from Oei Kim Boen, after a severe screening process and final acceptance by this master-teacher. At the conclusion of his training period and the passage of proficiency tests, Mr. Wetzel was awarded the order of the Golden Dragon, which he wore on the back of his uniform as a ceremonial indication of his standing in the school. The basic sequence of these levels, or awards, is as follows: white, green, silver, gold, and finally, black dragon, which is the highest level attainable and was held by Mr. Wetzel's teacher. Diplomas were not issued in Indonesia or China, since your level of skill was your real diploma and reflected back to your teacher. Until 1941 when WW II started, Mr. Wetzel traveled throughout Asia observing and practicing with students of other fighting methods. He incorporated into his own method what he saw and considered practical in actual combat situations. During WW II, Mr. Wetzel served as a member of the Royal Dutch Indonesian Army. In 1949 he moved to Holland, and in 1956 he immigrated to Vanport, Pa. In 1960 he opened a self defense course to the general public. In late 1961, I began taking instruction from him. At no time did Mr. Wetzel strike or hit any of his students in an attempt to gain respect or prove his superior ability. What he taught, how he taught, how he corrected our mistakes and showed us how to move to protect ourselves, convinced us that he was a genuine teacher of the ancient arts. A true teacher can and will guide and give direction to, not coach, his students. We considered ourselves fortunate to have had a teacher of his experience, background, and knowledge. Mr. Wetzel continued to teach until his death in 1975. The Poekoelan Tjimindie fighting arts are a selective blend of the ancient, original Chinese and the later Indonesian schools of the fighting arts. The Tjimindie fighting arts were developed on the island of West Java by two masters of these old arts. Chinese master Oei Kim Boen and Indonesian master Mas Djut (Jud). Over a period of three years these two practiced together many times. Gradually, the Poekoelan Tjimindie fighting arts were developed by combining the best of the two masters' knowledge and eliminating what was considered impractical in actual fighting situations. Poekoelan means "returning fists and feet." Tji means "beautiful" and mindie means "flowing waters." In China, Oei Kim Boen originally learned the ancient "soft" southern system and later traveled north where he studied the "hard" northern system, which he combined and practiced as one. In addition to these, he studied the monkey, crane, and Chinese tiger animal styles of fighting. In Southern China, the people are generally of slender build and do not have great upper body strength. Consequently, they parry "soft" with the palm and heel of their hands, and the inside and outside of their wrists, while at the same time leaning back away from blows aimed at their upper body. They also parry and block with their knees, shins, and feet or draw back their lead leg to protect it from attack. The lead leg kick is generally directed to the opponent's knee joint. This technique prevents the southern stylist from being overrun by the attacker. Body movement is forwards or backwards, and side to side, in a limited rectangular area of movement. The southern system is like bamboo. It gives with the force of blows, then snaps back hard and strong. On the other hand, the northern Chinese people are generally larger and have greater upper body strength. Therefore, they block "hard," with the closed fist and forearm, to protect their upper body. They withdraw their legs to protect their lower body. Body and arm movements are circular in nature with half-circle foot movements from square body positions. The northern system is much more mobile than the southern system. In Indonesia, Mas Djut was a master of the kilap (pronounced keep-lop) system, one of lightning fast striking, and the tiger and snake styles of fighting. The kilap system uses a series of linear strikes to overall body targets. The kilap exponent does not attempt to overrun his opponent with brute force or strength, but it dart in and strike at maximum speed to vital body targets. Since Mas Djut lived near the water's edge, he would often sail out to sea and back with Chinese merchants on their sampans. This is how he met Oei Kim Boen, who had migrated to Indonesia from Canton, China. Their fighting systems and animal styles were blended together and were called Poekoelan Tjimindie. The animal form chosen to represent these arts developed by the two originators was the dragon. The two masters of the ancient, original fighting arts physically possessed speed and power in their movements above average human capabilities. For example, they would utilize a form of hypnosis against their enemies. The ability to apply hypnosis effectively is a special skill which only the masters of the old arts possessed. By such means they were able to distract and confuse the enemy, and to cause him to misdirect his attacks, and to not trust what the saw or thought he saw. This hypnotic ability was adapted into fighting situations and is the reason old style masters were able to defeat younger and more powerful fighters. So while the masters physical condition declined somewhat with age, his mental abilities became more proficient from a lifetime of experience. Poekoelan Tjimindie is composed of a wide range of animal postures and movements. Animal mannerisms were included in Poekoelan Tjimindie because they enlarged human actions, thus bringing to them a much wider range of self-defense possibilities and applications. The monkey style from China is noted by its bent knee, wide leg positions (so defenders wouldn't have a leg broken by a knee-joint kick), with the body at a low height. Arm movements are circular with open hand parries, and closed hand grabs with palms down. Defensive body movements are side-to-side and forwards and backwards, with dodging head movements and body rolls across the ground when needed. The Crane style uses low to high one-legged body positions with turns. Every second or third move begins in a crane position, with a retreat covered by open hand parries, then follows with attacks or counterattacks. Kicks are delivered from high to low. The head rotates in all directions to watch for any oncoming attackers, providing a circle defense. The Chinese tiger form uses open hands with extended fingers to claw or rip at vital targets. The method is to hit or place with the palm to the target, then grab and pull. The snake style from Indonesia is recognized by the close foot positions and medium body height. Elbow-to-elbow distance is kept close to the body to protect the midsection from injury. By weaving the arms, body, and legs during retreats and attacks, the snake exponent appears to be giving in, but immediately redirects the fight to his advantage. From the fluid softness of motion, hardness of action appears as a silkiness, and flows along with the employment of abrupt and choppy blows. Fast striking occurs from any position with blows that are non-breaking, because only soft vital body targets get struck, such as the eyes, throat, and the groin. The Indonesian tiger style of fighting was perfected for defense on wet and slippery ground where more upright conventional body positions were not practical, and as preparation for the possibility of falling to the ground. The tiger stylist believes that his upright, standing enemy has but two foundations, his feet. On slippery ground these are obviously inadequate. However, the tiger exponent has more foundations- his hands, feet, knees, and body- combined with a lower center of gravity to provide him with supreme stability, while that of his enemy is shaky at best. This style is extremely deceptive since most conventional upright fighters would assume that the tiger stylist is helpless while on the ground. This assumption is almost always a fatal error of judgement. Kicks are delivered to the attacker's lower extremities when he moves in to attack, using a smooth movement with fast withdrawal of a weapon after impact. Striking weapons hit the attacker from front and sides, low to high, to break the attacker's legs out from under him. The tiger exponent makes good use of his teeth to inflict painful and possibly lethal wounds to the attacker. This is done once the attacker collapses to the ground with his legs, knees, and ankles broken, or shocked. The Indonesian tiger style is a very effective fighting method. In the Poekoelan style, correct hitting is invisible. Striking weapons are camouflaged by foot and hand movements, and always strike indirectly. The blow never starts or comes from the place the Poekoelan exponent is positioned for and never strikes the target it appears to be aimed toward. This deception is accomplished by having the arm or leg relaxed while it is on the route of travel to the real, intended target. In that way, the same weapon can hit multiple targets without withdrawing, and fools the opponent into blocking to protect a target that is not too be hit. Thus, the way is opened at another target that is going to be hit. Although powerful, a blow that is tense from beginning to end is not as fast, and can only hit the one target it is aimed for and come back to the original position it was thrown from. At close in-fighting ranges blows need only to be two or three inches away to be effective. This method of Poekoelan striking is called the art of the poison hand. Poekoelan Tjimindie makes good use of the head for butting action. Head on, side to side, and rear guard actions are effective in very close in-fighting situations, along with the use of elbows and knees. When you are this close to your opponent, elbows and knees are preferred, since it is impractical to attempt a long kick or punch at this distance. A small skilled individual using elbows and knees can actually "crash" right through a much larger and more powerful antagonist, actually knocking him to the ground. In some styles only low kicks are used while in others only high kicks are thrown. However, in Poekoelan a combination of the two is considered the best, since the attacker will never know where he will be hit next, or with what. When you kick or fake a kick high, it opens your opponent's lower body. Conversely, if you attack or fake low, it opens the attacker's upper body for a follow-through, and hopefully, the favorable conclusion of a fight. When an enemy is trying to severely injure you, or worse, take your life, there is no logical reason for giving him any advantage. Because of the lethal potential of actual street fighting., the Tjimindie exponent will seek to employ his hands, arms, feet, and legs in such a way as not to expose his groin and/or support leg to possible attack. Extremely high kicks render the kicker momentarily unstable on solid ground and much more so on irregular, slippery, or otherwise uncertain terrain. When very close to your attacker it is sometimes physically impossible to attempt this kick. Adding to this risk is the fact that a kick to an area high up on the attacker's body takes more time to deliver than a kick to a lower area. The high kick travels over a longer distance and the high kicker, while he is in an imperfect state of balance gives his opponent more opportunity for a counterattack. Any kick thrown to a high target is easier to anticipate, dodge, misdirect, or stop than a kick to a lower, more accessible target. Poekoelan Tjimindie is taught and employed as a naturalist system. The student is eventually trained mentally to use his self-defense instinctively, accomplishing several moves at once, without having to consciously plan each move, and not just by learning a fixed, set pattern or sequence of movement. Because Poekoelan fighting techniques possess the potential to take the life of the attacker, the ethnical and moral outlook of the sincere Tjimindie exponent is the desire not to be forced to kill an attacker but preferably, through the least amount of force to stop the attacker from hurting him, or worse. If, however, during the course of the fight the attacker's life is unavoidably taken from him, it is an extremely regrettable situation which brings no one honor and is never to be glorified. The Poekoelan Tjimindie fighting arts are a method of self-preservation only, and not a sport. It is an art because it is a combination of systems of parrying, blocking, kicking, and striking, blended with styles of movement adapted from animals. It is taught and governed by ethical and moral principles, without which no method of fighting can rise above the level of indiscriminate acts of roughneck violence and still be considered an art.